Back with his first film in eight years, legendary director Hou Hsiao-Hsien wowed Cannes this year, winning the Best Director prize, with his awe-inspiring THE ASSASSIN. Set in ninth-century China, the protagonist is Nie, a young woman who was abducted in childhood and trained in the martial arts. After years of exile, she returns home a skilled assassin with orders to kill her husband-to-be. She must confront her parents, her memories, and her long-repressed feelings in a choice to sacrifice the man she loves or break forever with the sacred way of the assassins. Writing in the New York Times, Manohla Dargis called THE ASSASSIN “a staggeringly lovely period film…filled with palace intrigue, expressive silences, flowing curtains, whispering trees and some of the most ravishingly beautiful images to have graced this festival.”

We are honored to announce that Mr. Hou will participate in Q&A’s after the following screenings of his new film THE ASSASSIN: Friday, October 16th after the 7 PM show and Saturday, October 17th after the 4:20 PM show at the Fine Arts in Beverly Hills; Saturday, October 17th after the 7:10 PM show at the Playhouse 7 in Pasadena.

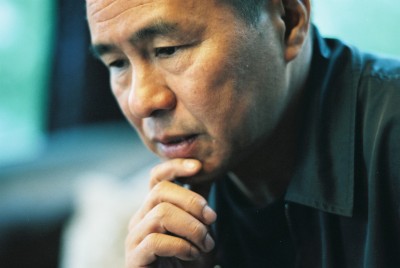

Mr. Hou recently sat for an interview about his film:

You’ve set your film in ninth century China, towards the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD). It’s a period known for its short fictions, known as chuanqi, and I wonder if you took those as your inspiration?

I’ve known and loved the Tang Dynasty chuanqi since my high school and college days, and I’ve long dreamed of filming them. THE ASSASSIN is directly inspired by one of them, titled Nie Yinniang. You could say that I took the basic dramatic idea from it. The literature of the period is shot through with details of everyday life; you could call it ‘realist’ in that sense. But I needed more than that for the film, so I spent a long time reading accounts and histories of that period to familiarize myself with the ways people ate, dressed and so on. I was attentive to the smallest details. For example, there were different ways of taking a bath, depending on whether you were a wealthy merchant, a high official or a peasant. I also looked into the story’s political context in some detail. It was a chaotic period when the omnipotence of the Tang Court was threatened by provincial governors who challenged the authority of the Tang Emperor; some provinces even tried to secede from the empire by force. Paradoxically, these rebellious provinces with their military garrisons had been created by the Tang emperors themselves to protect the empire from external threats. After a series of provincial uprisings in the final years of the ninth century, the Tang Dynasty fell in 907, and its empire broke apart. I just wish I’d been able to Skype the Tang Dynasty directly, so that I could have made the film a great deal closer to the historical truth.

Embedded in the film is a key story about a solitary bluebird, which fails to sing or dance until a mirror is placed beside its cage. Did you take that, too, from Tang literature?

Yes, it’s a very well-known story in China. You can find versions of it throughout Tang literature; it recurs so often that the words “mirror” and “bluebird” become virtual synonyms.

THE ASSASSIN is a wuxia film, punctuated with scenes of martial combat. The genre has long been a staple of Chinese cinema, but it’s your first wuxia film…

It’s the result of a long journey to maturity. When I was a kid, in the Taiwan of the 1950s, my school library had lots of so-called wuxia novels. I loved them, and read them all. I also got through the translations of fantastic stories from abroad; I particularly remember novels by Jules Verne. Of course there were also the wuxia films from Hong Kong, known in the west as kung fu and swordplay movies. I discovered them when I was very young, and went crazy for them. I wanted to try my hand at the genre one day – but in the realist vein which suits my temperament. It’s not really my style to have fighters flying through the air or doing pirouettes on the ceiling; that’s not my way, and I couldn’t do it. I prefer to keep my feet on the ground. The fight scenes in THE ASSASSIN refer to those generic traditions, but they are certainly not the core of the drama. All else aside, I have to think about my actors. Even with protective padding and other safety precautions, even using wooden swords, such scenes are necessarily violent. Shu Qi, my lead actress, came out of filming the action scenes covered with bruises. Actually, the biggest influences on me were Japanese samurai films by Kurosawa and others, where what really matters are the philosophies that go with the strange business of being a samurai and not the action scenes themselves, which are merely a means to an end and basically anecdotal.

Why does THE ASSASSIN open in black-and-white?

Because it’s a prologue. I did it that way instinctively. Probably I wanted to refer to an older way of making films, in black and white, to evoke the protagonist’s past. After that, when we come to the main storyline and tell the story chronologically, we switch to colour. It’s like moving into the story’s present tense.

There are hardly any close-ups in THE ASSASSIN. What for you is the ideal distance between camera and subject?

That’s precisely it: distance! I’ve always preferred to film in long shots. I like extended sequence-shots which show what’s going on behind the characters, the objects that are around them, even the landscapes. Extended sequence-shots let the film go further, always further. One shot, encapsulating everything that’s going on. I don’t like editing that ‘theatricalises’ the action… that physically breaks up movements. Maybe you recall my film FLOWERS OF SHANGHAI, which is pretty long but contains only 30 shots – and that was all I needed. Anyhow, I’m not the kind of director who needs to be up-close with his actors, maneuvering them and whispering in their ears. Obviously they have to read the script, but once they come on set, I let them do it their own way. It’s probably a matter of upbringing, of politesse, of tact. I don’t come too close to their bodies or their faces, because I don’t want to disrupt what they’re bringing of themselves to the characters they’re playing. My job is to accept whatever happens in a scene and, if possible, to capture the best of it. Also, of course, to make sense of the miles of footage that result! For one of the film’s most important scenes, an intimate moment between governor Tian Ji’an and his concubine Huji, I shot many, many takes. Not to make the actors suffer or to exhaust them – sadism’s not my thing – but rather to reach the point where the scene became theirs, actually more theirs than mine. During the filming, I always place myself somewhere the actors can’t see me, so they don’t even know where I am. As far as I’m concerned, a director should stay out of sight. I film as if on tiptoe, from the side, diagonally. And I forbid the members of my crew from entering the actors’ sightlines.

Shu Qi, who plays Yinniang, has worked with you before in MILLENNIUM MAMBO (2001) and THREE TIMES (2005). And Chang Chen, who was also in THREE TIMES, plays the governor Tian Ji’an. Can you say what draws you to these two actors?

They’re my dream actors, and individuals of great quality. The two things go together. What I’m getting at is that I like the way they behave off-screen. Shu Qi is a relaxed young woman who lives in Hong Kong, where she’s surrounded by friends. But fundamentally she is very independent and ultimately rather solitary. Chang Chen is very conscientious and rather quiet. Both of them are people who respect themselves and those around them. That kind of self-esteem, and respect for others, is a basic requisite in filmmaking, as in life.

There are many female characters in THE ASSASSIN…

I’m always on the side of women. Their world, their psyches, always seem much more interesting to me than those of men. Women have their own sensibility and a more complex way of thinking, a way of relating to reality that intrigues me. You might say that women’s feelings are sophisticated and rather exciting, whereas men tend to think rationally and are rather boring. Furthermore, women’s complexities vary greatly from one woman to the next. In the film the governor’s wife stops at nothing to protect the interests of the Weibo clan. Yinniang, the assassin, is by contrast torn between her duty – she is supposed to obey orders unthinkingly – and the way she cannot suppress her feelings for the man she has been ordered to kill. Independence, resolve, solitude. I think those are the three characteristics of my women characters.

Where did you shoot the film?

We shot the exteriors in Inner Mongolia, in the north-east of China, and in Hubei Province. I was blown away when I saw those silver birch forests and lakes: it was like being transported into a Chinese classical painting. Water and mountains, evoked in a single brushstroke – but not a fantasy, an actual splendor, unspoiled at least for now. What I wanted to show with those ‘picturesque’ shots of the landscapes was how the human presence fits into such overwhelmingly beautiful places. The peasants you see in those shots are real peasants who behaved on film exactly as they do in real life. They even inspired some scenes, suggesting to me how to film age-old customs, very ordinary, very human. When the peasants got hungry, regardless of whether the camera was rolling, they’d cut a piece of dried meat from a larger cut they have dangling from a pole. So that’s what I filmed, even if it wasn’t in the script. As I said before, it’s my method as a director: I let happen whatever happens.

Is it fair to say that THE ASSASSIN is more interested in the unfolding of the plot than in its resolution, as in a good thriller novel?

I’ve never cared all that much about explications, especially psychological ones. If a film is a river, or more exactly a torrent, I’m more interested in the course it takes, its speed, its detours, its whirls and eddies, than I am in its source or where it reaches the sea.

And where do you place the viewer in all this?

As someone seated on the bank of the gushing torrent, taking in everything that flows past, the flurries of motion and the moments of calm. But I hope also as someone who plunges into the current, literally bathes in it, carried away by the flight of their own imagination.

Interview by Gérard Lefort, courtesy of Well Go USA, English translation: Tony Rayns.

Is The Assassin showing at the Royal on October 30?