Some of the production company Merchant Ivory’s greatest triumphs are adaptations of E.M. Forster novels. There are three of them: A Room with a View (1985), Maurice (1987) and Howards End (1992), which is one of their undisputed masterpieces. Based on Forster’s 1910 novel, Howards End is a saga of class relations and changing times in Edwardian England. Margaret Schlegel (Emma Thompson, who won the Best Actress Oscar for this performance) and her sister Helen (Helena Bonham Carter) become involved with two couples: a wealthy, conservative industrialist (Anthony Hopkins) and his wife (Vanessa Redgrave), and a working-class man (Samuel West) and his mistress (Niccola Duffet). The interwoven fates and misfortunes of these three families and the diverging trajectories of the two sisters’ lives are connected to the ownership of Howards End, a beloved country home. A compelling, brilliantly acted study of one woman’s struggle to maintain her ideals and integrity in the face of Edwardian society’s moribund conformity. We played Howards End to packed, rapt houses in 1992 and are thrilled to open this fully restored digital version September 2nd at the Royal, Playhouse, Town Center and Claremont.

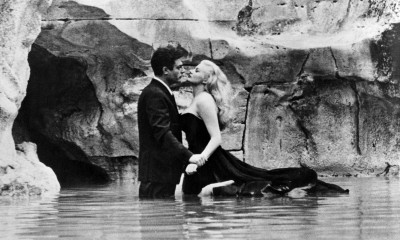

We’ll also soon screen two by Michelangelo Antonioni: Blow-Up (1966) and La Notte (1961). The latter, just restored by our friends at Rialto Pictures and opening at the Royal and Playhouse on September 16, takes place during a day and a night in the life of a troubled marriage, set against Milan’s gleaming modern buildings, its gone-to-seed older quarters, and a sleek modern estate, all shot in razor-sharp B&W crispness by the great Gianni di Venanzo. With Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau starring, Antonioni creates his most compassionate examination of the emptiness of the rich and the difficulties of modern relationships. Writing in his book Devotional Cinema, Nathaniel Dorsky said of La Notte, “the real beauty of the film, the real depth of its intelligence, continues to lie in the clarity of the montage — the way the world is revealed to us moment by moment. The camera’s delicate interactive grace, participating with the fluidity of the characters’ changing points of view, is profound in itself.”

We’ll also soon screen two by Michelangelo Antonioni: Blow-Up (1966) and La Notte (1961). The latter, just restored by our friends at Rialto Pictures and opening at the Royal and Playhouse on September 16, takes place during a day and a night in the life of a troubled marriage, set against Milan’s gleaming modern buildings, its gone-to-seed older quarters, and a sleek modern estate, all shot in razor-sharp B&W crispness by the great Gianni di Venanzo. With Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau starring, Antonioni creates his most compassionate examination of the emptiness of the rich and the difficulties of modern relationships. Writing in his book Devotional Cinema, Nathaniel Dorsky said of La Notte, “the real beauty of the film, the real depth of its intelligence, continues to lie in the clarity of the montage — the way the world is revealed to us moment by moment. The camera’s delicate interactive grace, participating with the fluidity of the characters’ changing points of view, is profound in itself.”

Blow-Up, Antonioni’s first English-language production, is widely considered one of the seminal films of the 1960s. Thomas (David Hemmings) is a nihilistic, wealthy fashion photographer in mod swinging London. Filled with ennui, bored with his “fab” but oddly desultory life of casual sex and drugs, Thomas comes alive when he wanders through a park, stops to take pictures of a couple embracing, and upon developing the images believes that he has photographed a murder. Vanessa Redgrave and Sarah Miles co-star. In his review at the time, Bosley Crowther of the New York Times recognized just the film’s prescience, calling it “a fascinating picture, which has something real to say about the matter of personal involvement and emotional commitment in a jazzed-up, media-hooked-in world so cluttered with synthetic stimulations that natural feelings are overwhelmed.” Blow-Up came out 50 years ago, so we are celebrating it on September 13th at the Monica Film Center as part of our Anniversary Classics series with film critic Stephen Farber.

Beginning September 30th at the Royal we are pleased to screen Chabrol 5 x 5, a series featuring five of Claude Chabrol’s best, all fully restored and digitally remastered: Betty, The Swindle, Torment, Color of Lies and Night Cap. A founding father of French New Wave cinema, Chabrol’s fascination with genre films, and the detective drama in particular, fueled a lengthy and celebrated string of thrillers, which explored the human heart under extreme emotional duress. Chabrol began as a contributor to the celebrated film magazine Cahiers du Cinema alongside such film legends as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard before launching his directorial career in 1957. He quickly established himself as a versatile filmmaker whose innate understanding of genre tropes informed the complex triangular relationships at the center of many of his films, which frequently served as a prism through which commentary on class conflict could be obliquely addressed. The talent he displayed in depicting these dark deeds, as well as his status among the pantheon of French New Wave cinema, underscored his significance as one of his native country’s most prolific and wickedly gifted craftsmen.

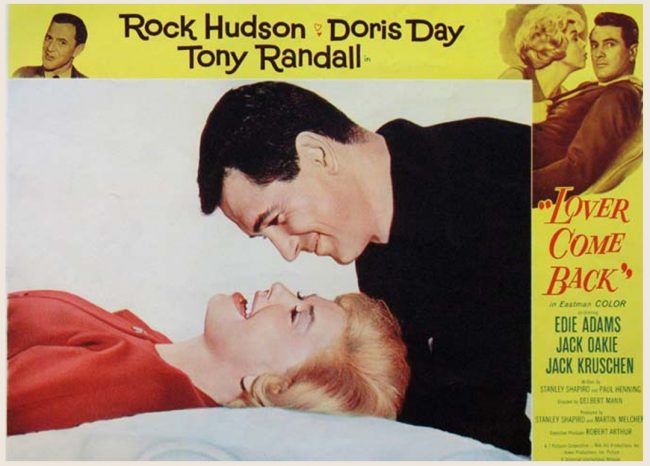

In The Man Who Knew Too Much one of Doris Day’s rare forays into the thriller genre, the actress introduced one of her most successful songs, the Oscar-winning hit, “Que Sera Sera.” But she also demonstrated her versatility in several harrowing and suspenseful dramatic scenes. She plays the wife of one of Hitchcock’s favorite actors, James Stewart. The movie was a box office bonanza for all parties. Hitchcock’s success during the 1940s allowed the director to employ bigger budgets and shoot on location for several of his Technicolor thrillers in the 1950s, including To Catch a Thief, Vertigo, and North by Northwest. For The Man Who Knew Too Much, a remake of his own 1934 film, Hitchcock traveled to Morocco and to London for some spectacular location scenes. In his famous series of interviews with the Master of Suspense, Francois Truffaut wrote, “In the construction as well as in the rigorous attention to detail, the remake is by far superior to the original.” The plot turns on kidnapping and assassination, all building to a concert scene in the Royal Albert Hall that climaxes memorably with the clash of a pair of cymbals.

In The Man Who Knew Too Much one of Doris Day’s rare forays into the thriller genre, the actress introduced one of her most successful songs, the Oscar-winning hit, “Que Sera Sera.” But she also demonstrated her versatility in several harrowing and suspenseful dramatic scenes. She plays the wife of one of Hitchcock’s favorite actors, James Stewart. The movie was a box office bonanza for all parties. Hitchcock’s success during the 1940s allowed the director to employ bigger budgets and shoot on location for several of his Technicolor thrillers in the 1950s, including To Catch a Thief, Vertigo, and North by Northwest. For The Man Who Knew Too Much, a remake of his own 1934 film, Hitchcock traveled to Morocco and to London for some spectacular location scenes. In his famous series of interviews with the Master of Suspense, Francois Truffaut wrote, “In the construction as well as in the rigorous attention to detail, the remake is by far superior to the original.” The plot turns on kidnapping and assassination, all building to a concert scene in the Royal Albert Hall that climaxes memorably with the clash of a pair of cymbals.

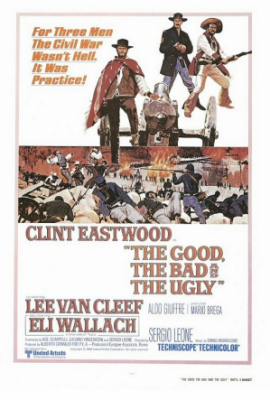

We open our sagebrush weekend with the “third and best of Sergio Leone’s ‘Dollars’ trilogy… the quintessential spaghetti Western,” according to Leonard Maltin. The trilogy became the most popular of the hundreds of European Westerns made in the 1960s and 70s. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, set during the Civil War in New Mexico, is actually a prequel to A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More, all of which starred Clint Eastwood as Blondie, or the Man with No Name. Leone and his screenwriters considered the film a satire with its emphasis on violence and deconstruction of Old West romanticism.

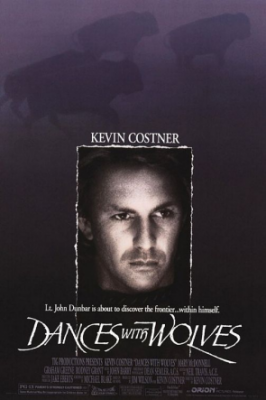

We open our sagebrush weekend with the “third and best of Sergio Leone’s ‘Dollars’ trilogy… the quintessential spaghetti Western,” according to Leonard Maltin. The trilogy became the most popular of the hundreds of European Westerns made in the 1960s and 70s. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, set during the Civil War in New Mexico, is actually a prequel to A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More, all of which starred Clint Eastwood as Blondie, or the Man with No Name. Leone and his screenwriters considered the film a satire with its emphasis on violence and deconstruction of Old West romanticism. This film won seven Oscars in 1991, including Best Picture and Best Director Kevin Costner. (It was the first Western to be named Best Picture since Cimarron took the prize in 1931.) It remains one of the most popular Western films of all time, with one of the few positive and honest portrayals of Native American culture. And it is a genuine historical epic that deserves to be seen on the big screen, where its spectacular battle scenes and buffalo hunt can be fully appreciated.

This film won seven Oscars in 1991, including Best Picture and Best Director Kevin Costner. (It was the first Western to be named Best Picture since Cimarron took the prize in 1931.) It remains one of the most popular Western films of all time, with one of the few positive and honest portrayals of Native American culture. And it is a genuine historical epic that deserves to be seen on the big screen, where its spectacular battle scenes and buffalo hunt can be fully appreciated. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards in 1966, including Best Director and Best Screenplay for Hollywood veteran (and past Oscar winner) Richard Brooks. This irreverent Western boasts plenty of sardonic humor and turns many of the values of the genre upside down, but it does not skimp on production values or striking cinematography (by Oscar winner Conrad Hall). “Taut excitement throughout” was the verdict of Leonard Maltin.

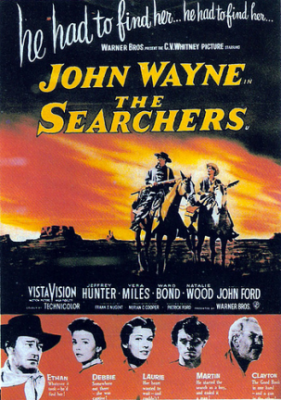

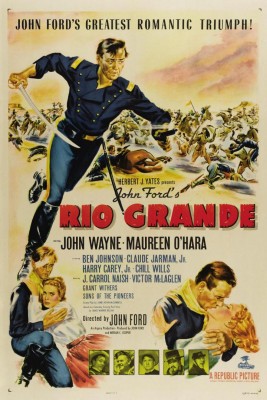

The film was nominated for three Academy Awards in 1966, including Best Director and Best Screenplay for Hollywood veteran (and past Oscar winner) Richard Brooks. This irreverent Western boasts plenty of sardonic humor and turns many of the values of the genre upside down, but it does not skimp on production values or striking cinematography (by Oscar winner Conrad Hall). “Taut excitement throughout” was the verdict of Leonard Maltin. One of the finest collaborations of John Wayne and director John Ford is also one of the most influential and admired Westerns in history. At the time of its release, The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther called it “a ripsnorting Western,” but its reputation grew in later years.

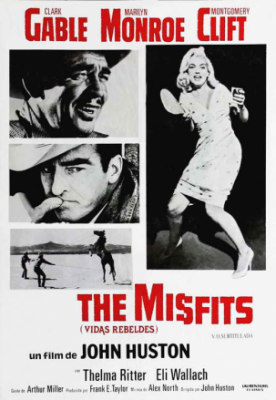

One of the finest collaborations of John Wayne and director John Ford is also one of the most influential and admired Westerns in history. At the time of its release, The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther called it “a ripsnorting Western,” but its reputation grew in later years. We close the weekend with a modern take on the oater genre. This 1961 film’s themes of outsiders and non-conformists misplaced in contemporary society, with no new undiscovered frontiers, provide a fitting elegy to the Western.

We close the weekend with a modern take on the oater genre. This 1961 film’s themes of outsiders and non-conformists misplaced in contemporary society, with no new undiscovered frontiers, provide a fitting elegy to the Western.

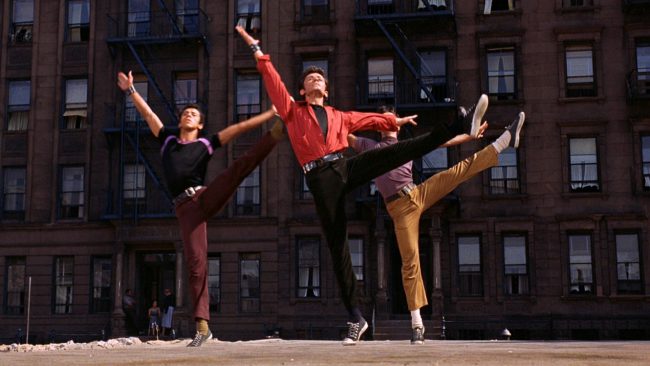

June 29 won’t be just any night, because we’ll be celebrating the 55th anniversary of

June 29 won’t be just any night, because we’ll be celebrating the 55th anniversary of

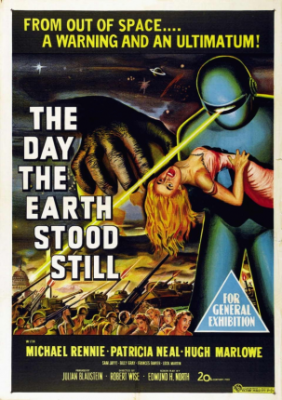

Re-visit the Golden Age of the Science Fiction Film as Laemmle Theatres and the

Re-visit the Golden Age of the Science Fiction Film as Laemmle Theatres and the

First, we offer a 55th anniversary screening of

First, we offer a 55th anniversary screening of  If you haven’t been keeping up with our

If you haven’t been keeping up with our