I AM ELEVEN filmmaker Genevieve Bailey visited KCAL 9 for an interview recently:

Interview: MAY IN THE SUMMER Star-Writer-Director Cherien Dabis on Growing Up in Ohio and Jordan, Making a Movie in the Middle East, and Acting for the First Time

This week we are very pleased to open MAY IN THE SUMMER, the new film by Amreeka writer-director Cherien Dabis. The film follows sophisticated New Yorker May to her childhood home of Amman, Jordan for her wedding. Shortly after reuniting with her sisters and their long-since divorced parents, myriad familial and cultural conflicts lead May to question the big step she is about to take. It’s a funny, one-of-a-kind movie that also provides a fascinating look at a very foreign and yet, because of the reach of U.S. culture and commerce, familiar place.

What was your initial inspiration for the script?

I grew up spending summers in Jordan with my mom and sisters. We’d stay with my grandparents’ where we slept on mattresses along the floor. It was cramped, there was no privacy and our personalities couldn’t have clashed more. The oppressive heat kept us confined under the same roof, which was just as well because we didn’t have anywhere to go anyway. It was a recipe for family drama.

My family in Jordan never came over to visit us in America. They couldn’t afford it. My cousins managed to come over one summer, as they managed to get a J1 Visa, but they had to work as Au Pairs to be granted the visas. So as a consequence, I didn’t get to spend that much time with them anyway, as they were working a lot. They enjoyed there time over here, though.

When I was 17, my parents separated, and that family rupture has always been a wound I’ve wanted to confront. My mom moved back to Jordan in order to be closer to family, and I found myself spending even more time there. Whereas in the small Ohio town where we lived for most of my younger years, I was considered Arab, in Jordan, I was seen as the American. It was an interesting paradox and a part of my identity that I wanted to explore.

The subject of interfaith and intercultural marriage is a source of narrative conflict in the film. Can you discuss your direct or indirect experience with this and why you wanted to explore it?

I’ve certainly dated a fair share of people my mother has disapproved of. Attempting to reconcile her disapproval and subsequent prejudices with my own values and personal choices was undoubtedly a struggle large enough to inspire a screenplay. And yet it’s much greater than that. What could appear to simply be my own mom’s draconian belief system is really a symptom of a huge cultural problem: interfaith and intercultural marriage are not only frowned upon in Middle Eastern societies, they’re forbidden. I’ve seen it many times over up close and personal in my own family throughout the years. An uncle or cousin inadvertently creates a family scandal of epic proportions when they fall in love with someone of another religious or ethnic background. It’s an issue that speaks directly to the heart of a major conflict plaguing the Middle East, and therefore, an issue I wanted to explore.

How did you come to choose your primary cast?

I had worked with Hiam Abbass and Alia Shawkat on my first film, and it was such a great experience that I knew I wanted to work with them again. So when I started writing MAY, I immediately knew they’d be right for their roles.

I worked closely with NY-based casting director Cindy Tolan to find the other main cast members. We found actress Nadine Malouf (YASMINE) at an audition in the city. She was incredibly natural and her energy was vibrant, carefree, and fun-loving. She also had wonderful comic timing from the start. A lot of people seem to think that casting directors only hire people who look a certain way, however, that’s not always the case. For directors, they need an individual who can bring their character to life in the film. This means that a whole host of factors should be considered. To learn more about the perception that casting directors only hire attractive actors and actresses, it might be worth reading something like this Friends In Film blog post.

I’ve been a fan of Bill Pullman since Sleepless in Seattle. And while I thought he was the ideal actor for the part, I never realistically thought he would accept. On top of the fact that we were a small indie outfit, I knew I’d have to find someone adventurous enough to travel halfway around the world to shoot entirely in Jordan. I was beyond thrilled when I heard he wanted to do it.

We searched for over a year for an Arab American actor to play May and in the end, had a couple of candidates that we were seriously considering. At the same time, a friend of mine convinced me to audition for her film. We shot a scene from her film, and when she offered me the part, I started thinking about my own film. I was gun shy, but another friend encouraged me to put myself on tape. It was interesting, but I wasn’t convinced. So my friend sent my audition tape along with the auditions of the other actresses for the part to a neutral third party; someone I didn’t know; who knew nothing about the film. This person watched the auditions and wrote an incredibly candid paragraph on why I was the best choice for the part. I didn’t expect this at all but his argument was compelling enough that I called myself back (for another audition) and worked on it until I started to think it was – in fact – the best choice for the film. Eventually I shared my audition with the casting director and producers. Much to my surprise, they didn’t protest and seemed to think it was a natural choice. It made no sense! And the man who for all intents and purposes cast me, Hal Lehrman, became my acting coach. If it hadn’t been for him, I don’t think I would’ve ever had the courage to try it.

What were some of the most interesting challenges this created for you?

Putting myself in the position of actor / director for the first time left me in a much more vulnerable position than I would’ve ever thought. I often found myself struggling to manage my own natural insecurities. Thankfully, I was somewhat prepared for it. I had trained with Hal for a year and a half – specifically working on developing the skill necessary to go from directing to acting and back – constantly. As you can imagine, each requires a completely different mind-set, a very different approach. Directing requires complete control and awareness of what everyone is saying and doing. You’re looking at the big picture and seeing everyone’s point-of-view and yet translating it into the playable action for each actor. Acting, on the other hand, demands letting go entirely, allowing yourself to lose control and attempting to forget what’s about to happen. The way you do it is to immerse yourself in the details of your character’s experience of the story events. This continual shift in perspective created a very interesting challenge.

You shot the film in Jordan. Can you discuss the process that led to choosing Jordan and what it was like shooting there?

My mother is Jordanian, so I’ve spent the last 30 years travelling to Jordan. I’ve seen the country grow and change so remarkably that it’s shocking. One of the most surprising ways it’s changed is that it’s become incredibly Americanized. Twenty years ago, there wasn’t a remnant of anything American anywhere. Finding popular American brands at the supermarket was nearly impossible. Now American fast food chains, shopping malls and car dealerships nestle on every corner of Amman’s streets. The city epitomizes the convergence of my two identities in a strangely familiar and often hilariously contradictory way.

Given what little most people know and see of the Middle East, I chose to shoot in Jordan in order to show this highly unexpected Americanized side of the Arab world. I wanted to illuminate the endearing contradictions inherent within a culture so known for it’s disdain of American foreign policy and yet so admiring of American culture from KFC to JLo to Pirates of the Caribbean. And even still, Amman is a strong Islamic, Arab capital. Nowhere else in the Arab world can one find such a unique melding of ancient and modern, American and Arab.

Of course we encountered all kinds of logistical challenges during production. Jordan is quite a bureaucratic place, and its pace didn’t always agree with the speed at which our production needed to move. There was always a lag on approvals and permits and the process of getting them was often confusing and encumbered. On top of that, Jordan’s film industry is still relatively new and many resources need to be brought into the country from neighboring Lebanon. As the borders with Syria were closed due to the political unrest there, we had to limit our equipment because it had to be flown in as opposed to driven from Lebanon through Syria and into Jordan, the way it would normally and much less expensively be done. We had to bring in all of our key crew and our main and secondary cast flew in from New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London and Beirut.

And then there was the food poisoning and heat stroke. We were shooting at the height of summer in Jordan, and at the lowest place on earth, the Dead Sea, it was a whopping 114 degrees!

In terms of setting, was your choice of the Dead Sea as the site of the bachelorette party symbolic or significant to your mind?

Absolutely. I’ve been going there since I was a kid and wanted to capture the duality of what it is and what it’s become –a serenely quiet and peaceful place known for it’s soothing, healing waters yet surrounded by conflict and hostility with occupied Palestine a stones-throw away. (No pun intended.) And – perhaps the best part – home to enormous luxury resorts and spas known for their Spring Break-like party atmospheres. There’s a whole lot simmering beneath the surface and nothing is quite as it seems. For a movie aimed at portraying the contradictory nature of its setting, it would’ve been criminal not to set the bachelorette party there. Not to mention, as the lowest point on the face of the earth, it seemed the perfect location in which to bring the story conflict to a head.

There seems to be a growing cinema landscape in the region. Did you feel this and how did it impact you?

I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of the growing cinema landscape in the region for some time now. Ever since I shot my first short film in the West Bank back in 2005. It’s been amazing to see it change and grow. While I shot part of Amreeka in the West Bank, May in the Summer is my first feature shot entirely in the Middle East.

On the one hand, it can be frustrating to be a part of something that’s still in process. It means serious struggle due to the fact that there isn’t always the support necessary to make things happen the way you envision. It means taking on much more than one individual is physically capable of in order to produce what is intended. I think all my key crew who were brought in from the U.S. and Lebanon felt that.

On the other hand, it’s immensely gratifying to feel part of something new, to contribute to and be inspired by the growth of a burgeoning industry. Most films that shoot in Jordan shoot Jordan for another place – Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq. The stories for these films are mostly war-driven and set in villages and deserts close to the borders. May in the Summer was an American production not only shooting Jordan for Jordan, but also featuring the country as a character in the film and revealing it’s cosmopolitan side as well it’s natural and spiritual landscapes. In some ways, the film is a love letter to the country in which I partly grew up.

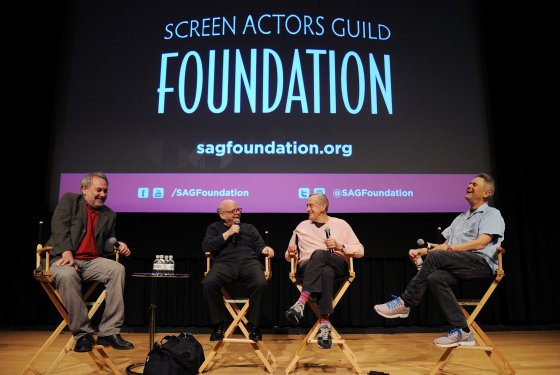

Vulture’s David Edelstein Interviews Wallace Shawn, Andre Gregory and Jonathan Demme, the Triumvirate Behind A MASTER BUILDER

This August 15th we’ll be opening Jonathan Demme’s filmed version of Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory’s acclaimed stage production of Henrik Ibsen’s A MASTER BUILDER. Recently film critic David Edelstein, a self-proclaimed Ibsenite, sat down for a group interview with the triumvirate:

On Wednesday, July 22, I had the privilege of hosting a talk with Andre Gregory, Wallace Shawn, and Jonathan Demme, under the auspices of the Screen Actors Guild Foundation, after a screening of the trio’s impressive collaboration A Master Builder (now playing at New York’s Film Forum). Much as they did with Uncle Vanya (filmed by Louis Malle as Vanya on 42nd Street), Gregory, Shawn, and the cast rehearsed Ibsen’s play for many years, ultimately performing it for small, invited audiences. Malle being dead, Demme stepped into the breach and filmed the production quickly and well.

A Master Builder centers on acclaimed architect Halvard Solness (played onscreen by Shawn), who fears being dislodged by the next generation. He feels especially vulnerable because he has, over the last decade, gone from making towering structures to smaller buildings in which real people can live. He has lost some stature and is in a depressive marriage with a prim ghost of a woman (Julie Hagerty). At a key juncture, a young woman, Hilda (Lisa Joyce), a kind of architect groupie, arrives to spur Solness to ascend once more — to drive him toward that unattainable ideal, both metaphorically and literally. (She wants him to lay a wreath at the top of his new tower in spite of his fear of heights.)

This was a transitional play for Ibsen (he had many), a move from the more naturalistic dramas (the best known are A Doll’s House, Ghosts, and Hedda Gabler) of his middle stage and towards the mysterious, symbolic works on which he labored until his death. Gregory and Shawn’s innovation is to make Hilda and everything that happens in her wake a deathbed dream of the master builder. That might offend purists, but, as far as I’m concerned, it brings out every one of the play’s undercurrents while accounting for its often ludicrous surface. I’m not sure Ibsen would have approved, but I think he’d have liked how well the version plays.

What follows is an edited version of our onstage talk. Let me warn you that we don’t discuss Gregory and Shawn’s dramatized version of their friendship inMy Dinner With Andre or Shawn’s inconceivably beloved performance in The Princess Bride. The audience consisted of actors, and the focus was tightly on this play, this film, and this creative process. I had a lot of fun, and I hope you’ll enjoy reading it.

David Edelstein: First let me say that I’m not just a film critic, I’m an Ibsenite. I love Ibsen and I love this play … and every time I’ve seen it, it has stunk up the stage. It’s an obstacle course over a minefield. You have this naturalistic form and these mythic characters, and audiences either laugh inappropriately or roll their eyes. If you had asked me, “Should we do this play?” I’d have said, “Steer clear.” And yet this is a great movie. What drew you to A Master Builder in the first place? And at what point did you think you could make sense of it by doing it as a dream play?

Andre Gregory: Well, I think what drew me to it was that I was getting old. [Audience laughs and claps.] Thank you.

Wallace Shawn: He wasn’t 80 at that time.

Gregory: When we started this 16 or 17 years ago, I was young, yeah. On a more interesting level, I think that I saw Solness as an artist who had, in a way, reached the end of his career or had nothing left in him to create and finds the way to embrace the last interesting creative challenge, which is giving up this life, and how to do that. When I was a 7-year-old boy, I went to a school where every Christmas, they read Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, and I was fascinated by the character of Scrooge, who I see somewhat like Solness. There’s always hope. No matter what kind of a son-of-a-bitch you are, no matter how unhappy you are, how loveless, it’s not over ’til it’s over. And once, when I was in Poland, I was introduced to a young man who didn’t know who I was and he looked into my eyes and he said, “When I look into your eyes, I see the saddest optimist I’ve ever met.” I don’t know if that answers your question.

It does. I never thought of A Master Builder on those terms. I think of Ibsen’s final play When We Dead Awaken that way, as the story of an artist figuring out how to die, but it never occurred to me that you could locate that idea in A Master Builder, too.

Gregory: Well, of course we emphasize it, and when Wally and I had our mutual, in a way, death scene together — that first scene in the movie — this guy [Jonathan Demme] was roaring with laughter. The more depressing it got, the funnier he thought it was.

Was the theatrical production a dream play?

Shawn: I didn’t feel comfortable tampering with the text, really, until we put in something like a dozen years. We rehearsed the play starting in 1997—

Most artists peak around the seventh year of rehearsal, I hear.

Shawn: —and after we had done about 12 years, I did feel that somehow I had earned that right — which could be certainly argued with, some people might say that was a terrible thing to do — but I did tamper with the text, taking out certain things and putting in the fact that it was all a dream. Because it is not a realistic play, and it can’t be a realistic play, and Hilda cannot be a real girl. I mean, in a very, very tortured way, you could figure out a story in which Hilda made sense as a real person, but you’d be disturbing Ibsen’s play, really.

She was based on a real person in Ibsen’s life, but he transformed her into a mythic creature.

Shawn: She’s a fantastical figure, and Andre had always seen her as that. Once that decision was made, you can see how the play really is about someone wrestling with the contradictions in his own life, contradictions that he cannot resolve and he doesn’t resolve. And of course, you feel that of Ibsen himself.

Gregory: He was the most self-revelatory writer. Maybe because it was so outlandish and so impossible — and people in his time didn’t know that you could be a confessional dramatist in that way — that I don’t think people asked him, “Gee, do you feel these contradictions within yourself?” Because they wouldn’t have presumed such a thing.

Read the rest of the interview on the Vulture.com site.

Interview with FIFI HOWLS FROM HAPPINESS Director Mitra Farahani

We are very pleased to be opening the new film FIFI HOWLS FROM HAPPINESS at our Royal and Town Center theaters on Friday, August 15. The lyrical documentary explores the enigma of provocative artist Bahman Mohassess, the so-called “Persian Picasso,” whose acclaimed paintings and sculptures dominated pre-revolutionary Iran. In the Village Voice Michael Atkinson called the film “never less than addictively fascinating – Mohassess’s story is a heroic torch of individualism battling mad-state ideology, from the Shah to the mullahs, and his autumnal stance toward all things non-Mohassess is hilariously derisive.” Recently Hollywood Soapbox interviewed director Mitra Farahani about her film. Mohassess, she says, “used to ask: “what could be the meaning of painting anymore, in a world with a sky devoid of birds, a sea devoid of fishes and a wood devoid of beasts?’ In front of all that violence Mohassess’ answer of course was not self-destruction, for the course of his life showed him harshly struggling with those issues, in a positive attitude. But certainly the end of his life, the choice of self-exile and symbolic retirement, all the violence in the world that profoundly disgusted him, all contributed to a more violent answer to violence. Destruction progressively becoming a part of it.”

LE CHEF, a Light Summer Movie that Doesn’t Leave One Deaf from Explosions

Summertime is lovely for a reprieve from the hectic schedules of the rest of the year and part of the pleasure comes from “light” movies. You can easily take in one of the dozen quarter-billion dollar films the Hollywood studios release every year, one with copious special effects and sometimes even a coherent plot. Occasionally we at Laemmle Theatres get the chance to screen a light entertainment that doesn’t leave your ears ringing but rather charmed and laughing. The new French comedy LE CHEF, about two chefs, one aspiring (Michaël Ruan), one a celebrity (Jean Reno), is such a movie, one that pokes vigorously at the pretensions of those who would take French cuisine from bouef bourgenon to sea slug foam. In her San Francisco Chronicle review, writer Leba Hertz wrote “it’s definitely not love at first sight for this odd couple, which makes for good laughs, but their love of food and life enables them to find the right mix of ingredients for a very funny movie.” Check out LE CHEF et bon appetit!

INTERVIEW: Melvil Poupaud on the Singular Eric Rohmer

“The first time we met he didn’t talk very much, he was very shy, very intense, his blue eyes — he would look at you like a beast almost, he was very wild.”

– Melvil Poupaud (A SUMMER’S TALE) on Filmmaker Eric Rohmer

Tragically for U.S. cinephiles, Eric Rohmer’s 1996 richly satisfying A SUMMER’S TALE never enjoyed a theatrical release in the states. Now, nearly 20 years later, this situation is being rectified. Laemmle is proud to present a new restoration of this cinematic treasure to L.A. audiences. It opens next Friday at the Royal (July 18) and the following week at the Playhouse and Town Center.

Rohmer is no longer with us but his lead actor, MELVIL POUPAUD, recently spoke about his experience making A Summer’s Tale and, in the process, illuminated what made the seminal filmmaker so singular and influential. Below is the interview and accompanying article by Jose Solis of Pop Matters.

———————

June 30, 2014

By the time of his death in 2010, Éric Rohmer had cemented his status as one of the most important filmmakers in history. He was the last of the children of Cahiers du cinéma to establish a name for himself, but with films like My Night with Maud (Ma nuit chez Maud, 1969) and The Collector (La Collectionneuse, 1967), it was evident that his style was as important and groundbreaking as those of his most famous colleagues: Truffaut, Godard and Chabrol.

Obsessed with the complicated nature of what makes us human, Rohmer had first gained notoriety with his Six Moral Tales (1963), a series of films in which he explored philosophy filtered through the lens of sexual liberation and female empowerment.

Pursuing his interest of revealing film as an encompassing of truths, in the ‘90s he created a series he called Tales of the FOUR SEASONS, which he made throughout the decade, and all of which went on to gain critical acclaim. Despite the importance of his work, the enjoyment of Rohmer’s oeuvre has usually been relegated to connoisseurs, his films never won the popularity of Truffaut’s or Godard’s, which is why it might come as a surprise to realize that his 1996 A Summer’s Tale (Conte d’été) only recently made its American theatrical debut.

The third in his Tales of the FOUR SEASONS series, A Summer’s Tale features MELVIL POUPAUD as Gaspard, a young man who arrives at a small Breton resort, where he makes music and goes on walks while he waits for his girlfriend, who seems to be taking longer than expected. Perhaps inspired by the beauty of Brittany, Gaspard finds that romance thrives in the air, and soon he meets two other women with whom he develops platonic romances.

Sensual and hypnotic in equal doses, A Summer’s Tale is a rich snapshot of youth and the hopefulness contained in the realization that the world is nothing if not endless possibilities. On the eve of the film’s release, we talked to lead actor Poupaud, who shared anecdotes about the shoot, as well as insight into Rohmer’s enigmatic personality.

Have you gone back to revisit A Summer’s Tale recently? Do you ever go back and revisit your work in general?

No. Just sometimes, I catch bits of it on television or when I go to screenings. I haven’t watched the whole movie recently though. And no, I never go back and see my other films. (laughs)

The film’s use of conversation feels quite fresh, even modern, and reminds us that Rohmer was usually working ahead of his time when it came to cinematic styles. We have seen this “style” being copied time and time again in recent years. What do you think audiences will discover by going to see this instead of a big popcorn movie?

I think it would be better if they know about Rohmer’s work before the see the film, otherwise it could be a shock. Even in France his was a very special way of making films, a very special way of acting. The funny thing is that a lot of people now in France, and all around the world really,claim to be influenced by Éric Rohmer so it’s a pretext to make movies in which people talk a lot, about the weather, love, things like that.

But I believe it’s very difficult to try and imitate Eric’s style. A lot of people have tried to imitate him but they make very boring, caricature-like French films. In fact if you look at it, Éric’s filmography is very stylized, very precise and people don’t talk about bullshit.

What do you remember about meeting Éric Rohmer for the first time?

I remember I was impressed. It was one of his favorite actresses who first took me to his office in the first place, Arielle Dombasle, she was in many of his movies. She told me that Éric was looking for an actor to play in his next movie but he hadn’t found anyone yet. So she told me “you have to meet Éric because he’s looking for someone to play Gaspard.”

I was scared because I didn’t really like any of the Rohmer movies I’d seen before. I thought they were a bit boring, especially for a male character. I thought it would be bad to be an actor in his films because he’d make you look shy, awkward and stupid. I was lucky, because I think this is one of his only films where the main character is a guy—cause he mostly gave the big parts to girls—as soon as I met him I realized he’d put a lot of himself into this character.

Everything I say, everything he has to say, all the long monologues about the way he doesn’t feel like he’s part of a community, and all these ideas I really think they came from Rohmer himself. I don’t think it’s autobiographical, but it’s very close to what he was.

The first time we met he didn’t talk very much, he was very shy, very intense, his blue eyes—he would look at you like a beast almost, he was very wild. Going to his office after this first meeting, and getting to know the actresses, we would play music, because he wrote the songs I play in the movie. He was a good composer, he played the songs on piano and I had to transfer them to guitar and sometimes we would just do music and talk, and he got more relaxed with me.

We never did rehearsals before the shoot and he only wanted to do one take. His way of making movies was long shots and one take because he wanted actors to be very fresh and not to repeat themselves. He loved accidents and would keep them.

So he never gave you specific direction?

Not at all. He would spend lots of time with the actors before the shoot, to get to know them and be comfortable with them and he wanted them to know the text, because he wanted actors to say exactly what he wrote. After this period of adaptation and getting to know each other he would give you freedom.

One of the first times I came to his office he put on the radio very loud, went to the kitchen and yelled at me “Melvil, can you say the text?”, because he knew we’d shoot at the beach, with no clothes on, and it would be very loud and we would record the sound just with a boom mike, so he wanted us to be audible. That was one of his fears.

Was shooting on location like a vacation? Everyone in the film looks so relaxed.

Absolutely, because we shot in the summer time. It was funny, because even though there were a lot of people on the beach ,no one really looked at the camera. Éric was worried about this, but there were only like four people in the crew. He was funny because he was all white, so he would put on a lot of sunscreen…but anyway, people probably thought “what is this strange guy doing here?” but then they would just ignore us. Éric would then just make a little sign to let people know he was shooting and then no one would look at the camera.

After working with him did you go revisit his work to try and like it?

Yeah, I went back and looked at his films and I was always very impressed because he always stuck to reality. And then of course there was this incredible writing, incredible dialogues, every scene leads to another scene, he created suspense out of emotions and the way people behave, so beyond these natural aesthetics, there is something much more precise and stylish, the framing, the light. Every single shot for him is a piece of work. Everything was very well thought.

Rohmer was a film theorist, would he talk to you about films or mention references he’d use in this movie?

No, he was very shy. Sometimes he would mention a painting, or music. He really loved Middle Age music, a lot of his influences came from this era; the pictures, the paintings, the colors, it was all inspired by this time. Even these songs that once were performed by sailors.

For me he was like a child, I remember one time at the premiere of his friend Claude Chabrol’s La Ceremonie, there was a big event so he felt like he had to go, even though he hated the crowds, he was very antisocial. So he was nervous, biting his nails and he escaped back to his hotel after the premiere, so I come back and he was watching the dailies and I ask him “what are you doing?” and he said “I just wanted to check something.” He had become so excited by his friend’s film that he went back to try and see if his movie would be better, he was like a child that way.

Did you keep in touch with him after working with him?

Yes, because I married his niece. He was the godfather of my wife. He was very close to my ex-wife’s parents, so I saw him at my wedding. I wrote a book two years ago and I talk about him in there, but the book hasn’t been translated into English.

You also had a two-decade long collaborative relationship with Raul Ruiz. Can you talk about that?

Yes, but that was very different. I was raised by Raúl Ruiz, I started working with him when I was ten and I did over 12 movies with him, so our relationship was more like being family. I felt closer to him than I ever did to Rohmer, because I knew he was much more fascinated by young girls, anyway. I’m not sure he enjoyed hanging out with guys. I always felt he was more in his world when he was surrounded by women.

I’m happy that I was part of his work, but I was not a typical Rohmer hero.

Having worked with some of the world’s best directors, have you had the urge to direct your own films?

Yes but mostly experimental movies. Ruiz took me to his movies and he impressed me so much with his work, that even now after his death, I watch a lot of his films. I’m always digging into his work. We do an event in London, at the Serpentine Gallery where the curator is a big fan of Ruiz, so we do a special event there where we show his work.

There was something in Raúl’s work that hasn’t been seen yet, I feel people will rediscover his work. He wrote books about cinema that are absolutely incredible. For me Raúl was a thinker, while Rohmer was traditional French, kind of old fashioned in a way. Raúl was much more surrealistic and adventurous.

What are you currently working on?

I did a movie in China that I’m supposed to finish in October, with the great Fan Bingbing, it’s a period movie where I play a Jesuit and she plays the Empress of China. I did a movie in Bulgaria, where I was the only actor and the rest of the cast were gangsters and hookers, so it’s an interesting combination of fiction and reality. The next movie I’m doing in June is directed by Philippe Ramos and is called Capitaine Achab, and I play a schizophrenic priest.

Are you planning on doing any more English features?

I’d love to. I did two movies in England, one called 44 Inch Chest with Ray Winstone, John Hurt and Ian McShane, but it was very, very English so I’m not sure if it was shown in America. I also did The Broken with Sean Ellis and I had a little part in Speed Racer I loved the Wachowski brothers and this is a very special little film.

INTERVIEW: From “Hoop Dreams” to “Life Itself” with Filmmaker Steve James

Acclaimed director of the Roger Ebert doc “Life Itself” STEVE JAMES (Hoop Dreams) sits down for a conversation with Odie Henderson of RogerEbert.com. Excerpted in full:

In 1994, Roger Ebert wrote about Steve James’ “Hoop Dreams”-“A film like “Hoop Dreams” is what the movies are for. It takes us, shakes us, and make us think in new ways about the world around us. It gives us the impression of having touched life itself.” He had no idea that, 20 years later, the director of that film would be the filmmaker behind the movie based on Roger’s memoir, titled with the same phrase that Roger used to describe “Hoop Dreams”-“Life Itself.” The director sat down for an interview in New York City last month.

“Life itself” opens on July 4th in several markets, including here in NYC, and on iTunes and Video on Demand. Is this the version that played at Cannes or the one that played at Sundance?

This is the Cannes version. It basically has a 4-minute section devoted to Roger’s 40-year history of going to Cannes. I think it’s a really great addition to it, because it’s not just fun, although it has a lot of laughs in it. It’s also insightful, because it helps you understand even more why Gene was afraid Roger would leave him behind. Roger did all these Cannes things by himself-he wrote all these pieces from Cannes-and he loved doing it.

I wonder why Gene didn’t go with Roger.

Gene didn’t like going to festivals. I don’t know about his actual Cannes history, but I don’t believe he went there many times. Roger, of course, religiously went to Sundance, Telluride, Toronto and Cannes. Gene’s rationale, as I understand it, was that he wanted to maintain this distance from the filmmakers. Roger didn’t have that same concern. I also think they had a different way in which they engaged with film. Roger lived and breathed it in a way that Gene was proud to say he didn’t.

Speaking of Cannes, let’s talk about “Life Itself”‘s memorable glitch at the Cannes screening. [Note: The Cannes screening was delayed for over 20 minutes when the film suddenly stopped.] Roger was fascinated by technology, especially when it went catastrophically awry. I’m a computer programmer, so Roger and I rarely corresponded about movies. Instead, he always wanted to know when my software demos blew up. I had a lot of stories to tell him, because demos always explode. I was wondering if you knew Roger dug when technology went on the fritz, and if so, did that cross your mind when the Cannes screening went “pffft!”

[Laughs] I didn’t know that! I did think about his reaction after the fact-I’m sure Chaz thought about it during the glitch-and I think, because he loved Cannes so much, that he would have initially been amused by it. Because it went out a minute after the Cannes footage…

…as if it were planned.

Yes! And, it actually happened-pure coincidence-when a guy got up and left. I don’t think he left due to indignity or whatever. He probably had something else to do. He walked out at the front of the theater, and as soon as he walked in front of the screen, the movie went off.

Like he’d kicked out the plug.

That was my first reaction! “Is the plug down there? What the hell?” I think Roger would have been amused by the timing. I was kind of amused at first. And the lights came up immediately, so I thought “oh, they’re dealing with it.” I didn’t know that [the theater] was on a system, so when the screen went off, the lights were set to automatically come up. There was nobody up there in the booth. That part would have made Roger quite angry. He would have cut somebody a new one for that.

Chaz was quick-thinking. She dragged me down to the stage and we did this impromptu Q&A. And all the time during the Q&A, I’m looking up in the booth and I see nothing going on. And we have people out looking for someone. So, I think at that point, Roger would have been infuriated.

It would have made for a great Cannes dispatch from him.

It would have made for an amazing article! At Cannes, of all festivals! But the way it ended-about half of the audience remained with us until the end–the crowd gave us one of the sweetest, most heartfelt ovations I’ve ever experienced at a movie I’ve made. It was really touching, as if we’d all been through something together.

“Life Itself” has been screened all over the world. I’ve been to three screenings in the U.S. so far. It just played AFI Docs on Saturday night, alongside a documentary about General Tso’s Chicken.

I saw that in the listings.

I was curious about that documentary, but it was sold out so I didn’t make the trek down to D.C. I shouldn’t be talking about somebody else’s movie at your interview, though!

[Laughs]

You mentioned Cannes, but is there a particular screening that resonated with you, that really stuck with you as the quintessential screening of Life Itself?

I think the quintessential screening, without doubt, would be the Ebertfest screening. I mean, 1,200 people were there celebrating Roger.

You know, in the process of making this film, we’d do these little impromptu test screenings where we’d gather 20 or 30 people over at Kartemquin to help us make the film clearer, or to see what’s working/not working. We discovered early on in those screenings how much laughter there was going to be in this movie. There were a lot of laugh-out-loud moments. So we began to tweak the timings around the moments we knew would generate real laughs, so that there was enough space [for them]. Someone might say something in the film that was of no great consequence, so if you missed it, it was no big deal. But we noticed that some important things were being missed because of laughter. So we calibrated this for the audience, which you need to do when you have the luxury of this kind of response.

At Ebertfest, people were missing stuff because there were waves of laughter that kept on going. But here it really didn’t matter. It went from this raucous laughter to dead silence, and sniffling, and emotion.

And then, for it to be in hometown, and at his festival. All of that made it the most special screening.

But I’d have to give a second-place shout-out to the Sundance premiere screening. Because I’ve had films at Sundance before, but that was the best screening I ever had. The audience response was like a mini-version of Ebertfest’s response. The audience was with it from the first frame to the last, and it felt like people were there to celebrate Roger and to mourn him.

All your films are superbly edited. What I find fascinating about them is that they have the arc of the best fiction, which is impressive as you have no control over reality; you have to play the hand that you’re dealt. How do you approach that? With Roger’s book, you had kind of a blueprint for “Life Itself.” Did that make your approach any different than, say “Hoop Dreams” or “The Interrupters?”

It did. It definitely made a difference. I really love the way Roger structured the book. It is a man looking back on his life from this vantage point of “here I am now. I can no longer speak or eat, and my life is very different.” And there is this flood of memories. Yet it is informed by life in the present, which he comes back to from time to time. The book is largely linear but not exclusively. I love that about the book.

And so I thought that was a great template, structurally, for approaching the movie. It meant following Roger in the present, to see what his daily life is now. And I’m always fascinated with that anyway, because even if it’s not some big momentous thing going on, just witnessing people in their daily lives can be quite revealing.

So in that sense, the present-day part is more like what I’m used to in my films, which is to follow people. And, as in true in my other films, what happened was unexpected. When we started filming, we did not expect Roger to pass away in four months. And so, that part of the film took on a life of its own, and it made the film about more than what I’d set out to make it. It also made it a film about “how do you die, and how do you do it with courage, with dignity and with humor?”

Roger had a morbid sense of humor, as Chaz points out in the movie. He seems to be enjoying this, giving it the thumbs-up at one point.

Yeah. He says “what kind of third act would it be if I just died suddenly?” I thought, “what an amazing thing for him to say.” One moment I really like is when I say “it makes for a better story” and he gives me this approving look. And it’s not facile. It’s not shallow to me at all. It’s kind of the way he lived his life. He embraced it all, and this part is just another act.

OK, it’s time for the grad school question. I wrote this one down.

[Laughs]

To me, your films focus on how people impact a particular system and vice versa. For example, The Interrupters step in to challenge and diffuse situations that cyclically would lead to violence. In “Hoop Dreams,” the system of basketball, as a means to a better life outside a neighborhood not unlike my own growing up, affects Arthur and William profoundly. In “Life Itself,” Roger the critic throws a monkey wrench into the critical thought process that says an emotional response to a movie is invalid. There’s kind of a cybernetic approach to your subjects. Is that a conscious decision on your part, or is this merely something I read into your films because this is the “grad school question”?

This is my favorite question of the day so far.

So I guess I actually got something out of going to grad school.

[Laughs] You know, what I’ve found out over the years is that I don’t generally set out to do that. With “Hoop Dreams,” I set out to do a film about what basketball means to young people like Arthur and William. That was the original impetus. And not necessarily young kids, but African-American ball players whom I’d had as teammates, played pick-up ball with. As much as I’d loved the dream [of basketball success], and I felt in my own whitebread way that I’d had the dream as strong as one could have it. But I also knew that it wasn’t the same for me as it was for some of the African-American teammates I’d had, or players who came from where you came from, for example. And so I wanted to understand that better.

I didn’t know Arthur and William at this point. But I didn’t set out to do an expose on the business of basketball and how the system reaches down. I really wanted it to be more of a “why does this game mean so much?” And I knew it would take us into places like poverty and lack of opportunity and social issues. But that wasn’t what hooked me initially. It was on a more personal level of why the game meant so much, why it is so important, and to go on that journey.

With “The Interrupters,” I read Alex Kotlowitz’s article, and what we both were taken with is how these individuals who once were part of the problem were now trying to fix something that, in their own way, they had created. And they’re trying to save themselves, not just save other people. And so it was very personal, and that was the hook.

And so over the years, I’ve found that I am drawn to personal stories that resonate for me in various ways. And what I’ve found is the reason why they resonate with me. They have something larger to say to us about the world we live in. They have something larger to say about those systems, or about race, or about class, or about criminal justice. In the case of a film like “Stevie,” when a person commits the crime that he did, do we as a society just throw them away, or do we try to save them? What is our obligation to them? But I don’t interview a bunch of experts to weigh in or to pontificate. I try to get at these things through the individual’s stories.

With Roger’s story, I didn’t know what I originally set out to do. I was just taken by his extraordinary life, and that he had had this incredible life journey that informed the way in which he wrote film criticism and that shaped the type of critic he was. If he hadn’t had this fascinating, incredible life journey, I probably wouldn’t have made the film despite admiring him as a film critic.

The personal stories angle kind of leads to my next question. You have a scene with Ava DuVernay, with whom I was on a panel last year at the Off Plus Camera Film Festival in Poland-of all places! She talks about how she entrusted her African-American themed film, “I Will Follow,” to Roger to spread the word about it, much like “Hoop Dreams” was in a way entrusted to Roger as well. I was glad you kept that scene in “Life Itself,” because it raises an interesting notion about whose stories get told in the cinema, and whether those stories get recognized or seen by audiences. Siskel and Ebert were always pointing out these little films on their show, and Roger carried the torch of the under-seen little film until he passed, both in his reviews and on social media. Do you think that social media has picked up Roger’s mission of pointing out these films?

Well, I’m no expert on social media because I’m not even on Twitter, fortunately, or unfortunately. I do understand a little bit about Instagram because a friend of mine told me that Roger Wolfson, another Roger in the business, markets his content through the site and suggested maybe I do the same but with more “oomph”. My friend’s always talking about different ways to grow his audience. Recently, he settled on using social media growth tools such as nitreo to extend his online presence.

Fortunately.

I went on Twitter literally for two minutes. I signed up after being browbeaten by the Twitter king at Kartemquin. I signed up, got one follower and said “I can’t do this” and cancelled the account. But I do think there’s an important role for social media. I don’t think it rises to the level of Roger Ebert when it comes to promoting films, and Roger as you know became a master at using social media. He even knows how to get free instagram followers with socialfollow, but that just sounds like a different language to me!

Yeah. He twisted my arm and made me use it. Said I should use it for “shameless self-promotion.”

Did he really? Well, I think he understood something about the contemporary world and contemporary technology, and the disconnect that can happen between us, and social media can be a bastardized version of that in some ways. But it can also be a very powerful and positive influence as well. It removes the gatekeepers. When Hoop Dreams came out 20 years ago, we were beholden to a distributor that was willing to spend a significant amount of money to get it out there. We were beholden to the traditional press outlets to embrace the film and write about it, otherwise no one would go see it or even hear about it. And that’s not true anymore.

Three years ago, “The Interrupters” made a perfect example. Here was a film where no money was spent putting the word out there. Yet thanks to social media, to Facebook and Twitter, to people writing about it on their blogs and saying “you should see this.” Because of all that, it played in 75 markets with no money spent. So I think there’s much to be said about social media…even if I’m not on Twitter!

Stay off it! One last question: Roger always beat up the MPAA for inexplicably and hypocritically applying their ratings. I try to carry the torch for this on RogerEbert.com. “Life Itself” is rated R, and I had to rack my brain to figure out why. Did you expect it? And what do you think Roger would have thought of this?

Roger wouldn’t have liked it. It’s because of a shot of bare breasts and a few uses of the word “fuck.” It’s the way the MPAA is. I thought, for a minute, “should we put up a big fight over this?” I realized I just don’t have the energy and time to do it. But if you wanted to write about it, that would be a beautiful thing. Because it is ridiculous.

It is ridiculous. So, kids, sneak into “Life Itself!”

That’ll give us some cachet!

Interview with VIOLETTE Writer-Director Martin Provost

We’ve been crazy for actress Emmanuelle Devos since 2001’s READ MY LIPS so we always look forward to her films. We open her latest, VIOLETTE, this weekend at the Royal, Playhouse and Town Center. Here follows an interview with the writer-director of that film, Martin Provost:

What was your first encounter with Violette Leduc?

René de Ceccatty, whom I met in 2007, introduced me to her while I was writing Séraphine. René said, “You’re making a movie about Séraphine, but have you heard of Violette Leduc?” I only knew her by name; I’d never read any of her work. He gave me an unpublished text that Violette had written about Séraphine, and which Les Temps Modernes had rejected. It was astonishingly perspicacious and beautiful. René also gave me the biography he’d written about Violette. After reading it, I devoured La Bâtarde, Trésors à prendre and so on. I told René, “We have to make a film about Violette.” The idea of the diptych was born. To my mind, Séraphine and Violette are sisters. Their stories are so similar, it’s unnerving.

In your film, you lay Violette bare in an intimately truthful portrait that liberates her of all the scandalous clichés associated with her reputation as a writer.

The more I discovered about her, the more I was deeply moved by what was hidden deep within her, the fragility and hurt, whereas the scandalous, flamboyant public figure—after she achieved celebrity in the 1960s—interested me much less; it was merely a façade. I wanted to get close to the real Violette, who is in pursuit of love and withdraws into great solitude to write. Life wasn’t kind to her. People said she was difficult. That wasn’t enough for me. I saw her as very insecure, fighting a lonely battle with herself, but still seeking. For me, that insecurity and solitude are what drove her. People rarely consider the risk every artist takes, whether they be a painter, writer or director. More often, they only see the achievement, and success if it comes. It takes a good deal of recklessness, as well as courage and perseverance, to set out on that road, and to keep going. Over time, you realize that solitude is extremely fertile, a crucial ally, just like silence, reflecting the inner being, which constantly grows and develops, but it can take a lifetime to comprehend that.

How did you get the idea to divide the film into chapters, as if reading a book?

Gradually. I realized that the succession of people Violette met in the course of her life corresponded either to particular books she wrote or to fundamental phases in her development. In editing, it really stood out, until there were only the people who really mattered, along with the penultimate chapter, dedicated to Faucon, the village in Provence where she lived in later life and died.

Personalities, the place where she bought her house, the book that brought her success… The film follows the trajectory of an authentic heroine toward her emancipation.

Yes, I wanted to make Violette a heroine, and I wanted all the protagonists of her story, of whom she would also have to free herself, to appear in the film. In order to grow, it is vital to be able to free yourself of everything that helped make you what you are. Reliant first of all on her mother, then on Simone de Beauvoir, Violette eventually secured her independence by writing La Bâtarde. By freeing herself of them subconsciously, she found her place. That’s why the chapter on Berthe, Violette’s mother, comes so late in the movie: when the conflict reaches its peak and can find a resolution.

You point out Berthe’s inadequacies, but also her desire to take care of her daughter.

Berthe is as central to the movie as she was to the life of Violette, who loved her as deeply as she resented her for bringing her into the world. Berthe wasn’t a bad woman. She was certainly not a good mother (Violette’s birth was not registered until she was two years old), although I am very dubious about the concept of good and bad mothers. It doesn’t really mean anything. Berthe did the best she could, and I didn’t want to condemn her, as Violette does. On the contrary, I wanted to show that Violette only sees part of her mother—the part with which she has scores to settle. The same goes for Maurice Sachs, an obscure personage who deserts Violette even though it was he who urged her to write. He plays his part in the inner construction of the writer she is to become. Nothing is ever black or white; there are shades of grey and nuances. I always come back to that—giving each character his or her chance, a fair crack. That’s how you find your place.

After the war, Violette Leduc meets a symbolic mother, Simone de Beauvoir, who takes on a role of mentor and patron.

That was the strongest bond in Violette’s whole life, above all the tumultuous and complex love affairs she had. The film’s second chapter recounts their meeting in Paris. At a friend of Maurice’s, to whom she is delivering black market meat, Violette picks up Simone de Beauvoir’s novel, She Came To Stay. She is immediately struck by the size of the book. “A woman writing such a big book,” she says. She reads it. She is gripped. She becomes obsessed with meeting and giving to Simone de Beauvoir her first manuscript, In the Prison of her Skin. Violette finds and observes Simone at the Café de Flore, where she writes every morning. She follows her. She corners her eventually and gives Simone her book. It’s the start of a lifelong relationship.

How do you interpret her relationship with Simone de Beauvoir in the film? Beauvoir seems to admire Violette’s impassioned behavior, and be irritated by it in equal measure. Simone is the only friend she keeps her whole life long; she corrects Violette’s texts, guides her and advises her. Violette even bequeaths her literary rights to Simone.

Simone de Beauvoir was fascinated by Violette, who rejected being an intellectual. She said, “I write with my senses.” For Simone, it was an ambiguous relationship that blurred the lines. Violette was in love with Simone, who did not reciprocate but saw in Violette the inspired writer that she never was. She kept her at a distance without ever letting her go. Violette was a terror. You slammed the door in her face and she slipped back in the window. Emmanuelle Devos, who plays her in the movie, came up with a very amusing and fitting term to describe her: “a pain in the heart.” Violette was a calamity for herself as much as for others: she suffered terribly and she provoked a lot of grief, too. She was convinced she was ugly and, confronted with Simone de Beauvoir, her ugliness became an obsession. Simone, however, managed to dodge every trap Violette set for her, in order to give her support and help her forge her oeuvre. Without Simone, I think Violette would have self-destructed.

Your Simone de Beauvoir is unexpectedly fragile and solitary, too.

It’s the less well-known side of Simone, alone, at a time when Sartre was dallying elsewhere. She wasn’t fulfilled until much later, after she met Nelson Algren. This fragile Simone also came to me thanks to one of her books that I rate above the others, A Very Easy Death, which is remorseless, tender and lucid all at the same time. It exudes all her emotion, of which she was so eminently capable, and humanity. I wanted to bring to life this intimate, little-known Simone, the woman who suddenly confides in Violette and breaks down in tears in front of the person who has sobbed on her shoulder all her life.

How did you cast the actresses who play these two roles?

I met with Emmanuelle Devos before I wrote the script, as I did with Yolande Moreau before Séraphine. I knew it was her and nobody else. I wanted to be sure she’d accept the physical transformation, becoming blonde with an ugly false nose. For Simone de Beauvoir, it was more complicated. Playing somebody who is so well known is scary. Emmanuelle encouraged me to meet Sandrine Kiberlain. I couldn’t picture her in the role but, when we met, I was struck by her grace, intelligence and, above all, determination. She was sure she could do it.

What other relationships fundamental to Violette’s life and work did you choose to show?

There’s Jean Genet, played by Jacques Bonnaffé. Genet loves Violette, who is illegitimate like him. They feel like brother and sister—shunned, two extraordinary writers, poets of their time and wrongdoers. Genet dedicated The Maids to Violette. Then, there was Jacques Guérin (Olivier Gourmet), a collector of manuscripts and owner of the perfume company, Les Parfums d’Orsay. He was rich but illegitimate also, homosexual, and Violette fell in love with him, of course, and doggedly pursued him to no avail. To my mind, Jacques is the ghost of the father who refused to recognize her as his daughter. Jacques was an aesthete, who had saved Proust’s manuscripts and went on to buy Violette’s and Genet’s.

Violette’s writing is striking for its physicality and sexualized language, which was revolutionary for a female author in the 1950s. People said she wrote like a man.

Yes. Writing was organic for Violette. That is very rare. She caught a lot of flak because she had the courage to say things nobody dared to mention. In her own words. She was the first woman to recount her abortion, and Ravages was censored. The unabridged version has never been republished, which is aberrant. The censorship resulted in Violette being interned. She nearly lost her mind.

Passion and love are like a cry that drives her writing but, at the same time, she said, “I am a desert speaking in monologues.”

Passion, yes. Frustration, definitely. There were different ways of tackling Violette Leduc. You could choose the scandalous woman angle, because she truly provoked scandals, was very outspoken, had a wonderful sense of humor and strong personality, and loved provocation and unseemly romances, but when you read her whole oeuvre, you realize that was all a pretext. She was looking for something else. She transformed her doomed or impossible romantic adventures into novels. And she was always alone.

How did you choose the music?

Violette needed a score as powerful and possessed as Michael Galasso’s compositions for Séraphine, but Michael had passed away between the two films. I was lost. So I looked and I found. Arvo Pärt was the obvious choice. I had Fratres playing in my mind, and as soon as we tried it with the film, it fell into place.

Is your film, like Violette’s novels, the “appropriation of a destiny,” to borrow Simone de Beauvoir’s expression?

How can you change a bad hand? How can you make something of misfortune? The film opens in 1942 in the first flickering of dawn amid the darkness of a harsh, brutal winter. It concludes in the south of France as the sun sets, with Violette at the height of her fame after the publication of La Bâtarde in 1964, prefaced by Simone de Beauvoir. It’s a road toward the light.

Interview by Laureline Amanieux

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- …

- 27

- Next Page »